This guide will provide an overview of the calculations and formulas involved in hydrostatics and ship stability, as well as their importance in marine engineering.

In the marine industry, calculations hydrostatic and stability of Ships are widely used in the ship design phase;

Hydrostatics studies the buoyancy forces and geometrical quantities related to the hull; stability considers the ability of a ship to restore itself after being tilted by loads or waves.

Explain the conventional symbols in the formulas for calculating ship hydrostatics and stability.

Basic quantities

Center of gravity G: point of application of the total gravity force of the ship.

Center of buoyancy B: point of application of the Archimedes thrust force; changes when the ship is inclined.

Metacenter M: intersection of the vertical line through B when inclined with the initial longitudinal axis; used to evaluate initial stability.

Metacentric height GM: initial stability index, calculated by the formula 𝐺 𝑀 = 𝐵 𝑀 − 𝐾 𝐺 , in which 𝐵 𝑀 = 𝐼 𝑉 with 𝐼 is the moment of inertia of the cross-section of the submerged part and 𝑉 is the volume of the submerged part; GM > 0 usually indicates positive initial stability.

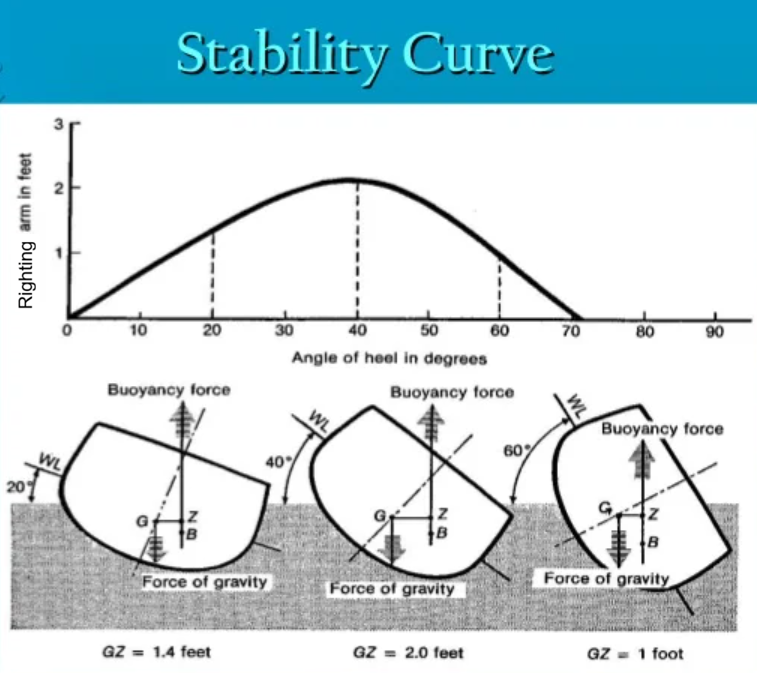

The righting arm and the GZ curve

The righting arm GZ is the horizontal distance between G and the vertical line passing through B when the ship is heeled;

The GZ (heel angle) graph shows the restoring moment versus heel angle and is an important criterion for assessing stability at larger angles (not just GM).

Other hydrostatic curves such as mass curves, hydrostatic sections, and moment curves are used to calculate allowable loads and launching behavior.

These calculations are important during ship operations, especially during loading to ensure that the load is properly distributed to maintain stability.

It involves a variety of calculations, including the ship’s displacement, center of buoyancy, metacentric height and stabilizing levers.

Besides marine engineering, the concepts of hydrostatic and stability are also relevant in offshore engineering, especially in the design and construction of oil rigs and other offshore structures.

These calculations are to ensure that the ship can carry its intended cargo safely and stably without capsizing.

Influencing factors and risks:

Offset loading (cargo, fuel, water) changes KG and can reduce GM. Free surface effect of the tank reduces actual stability; compensation factor must be calculated.

Flooding changes the shape of the submerged section and B, which can lead to instability; safety standards require damage stability checks.

Basic calculation approach

Determine the submerged geometry, calculate the volume V and the moment of inertia I.

Calculate 𝐵 𝑀 = 𝐼 𝑉 and know 𝐾 𝐺 from the mass distribution → calculate 𝐺 𝑀 = 𝐵 𝑀 − 𝐾 𝐺.

Calculate the GZ curve according to the tilt angle to evaluate the restoring moment at large angles.

Check the operating limits: minimum GM, maximum GZ, and area under GZ curve according to the design standard.

Consider the free surface effect and damage scenario if damage stability check is required.

Anothers important application

Modern-day cruise ships are designed with very high stability standards to ensure the safety of thousands of passengers and crew members onboard.

Ship’s hydrostatics and stability are not only applicable to seagoing vessels but also to submarines. It is critical in controlling the buoyancy and balance of submarines.

Conclusion

Ship’s hydrostatics and stability are essential components in marine engineering and naval architecture, ensuring the safe and efficient design and operation of ships.

The ability to perform precise calculations related to the buoyancy and balance of a ship is vital in preventing catastrophes at sea.